Thursday 7 Sept 2023 | 5pm Official Opening

Friday 8 Sept – 18 Sept 2023

Viewing by appointment only

more info : hello@superbroadcast.com

whatsapp : +65 8501 4359

Sunar Sugiyou

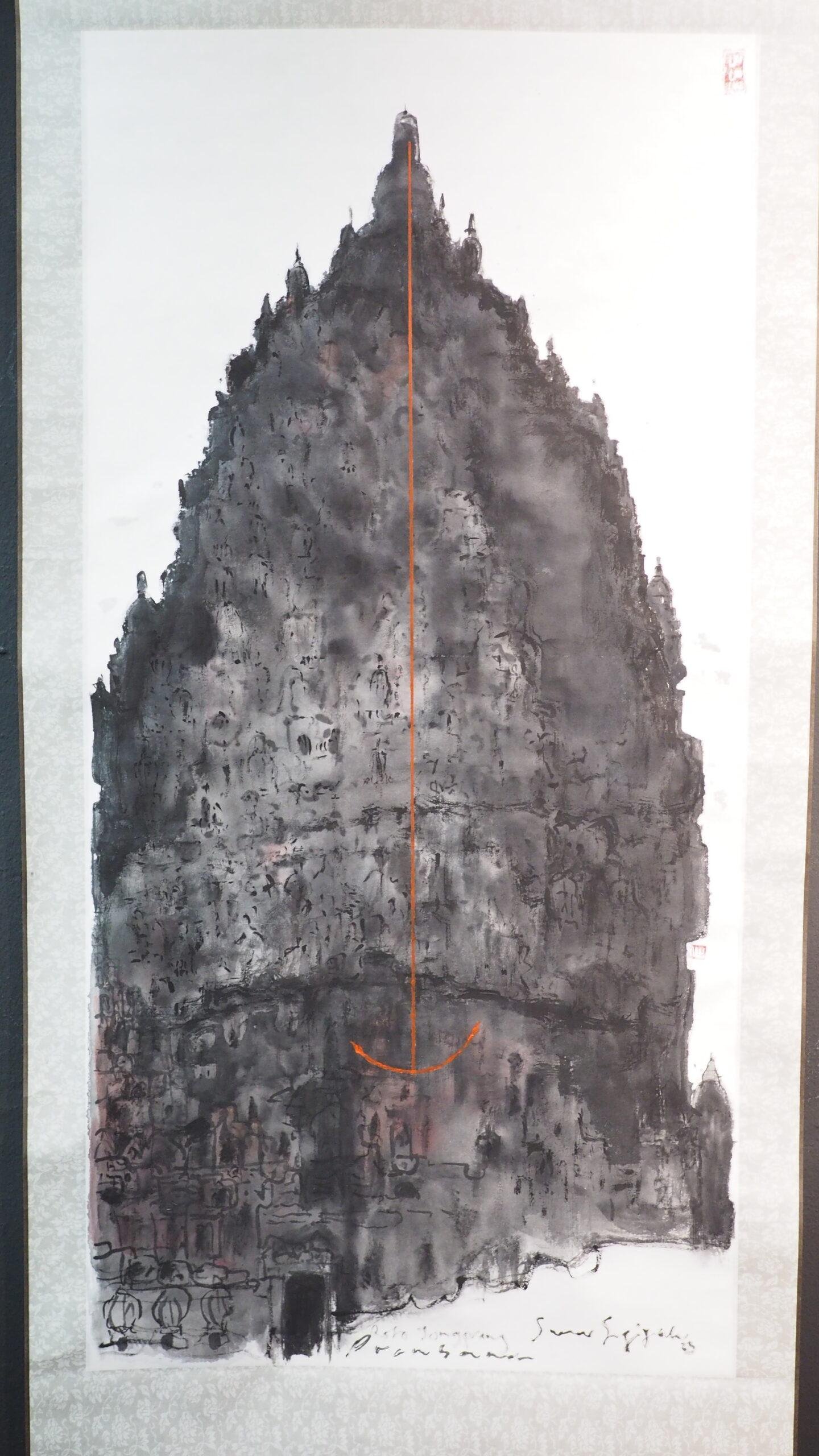

Sunar Sugiyou (b. 1962, Singapore) has been touted as Singapore’s “prodigal artist”. Initially starting with oil on canvas, he slowly developed his unique style using the technique of Chinese brush painting on Japanese rice paper. It is this series of works that showed his true calling. Though his art displays elements of Malay culture reflecting his Javanese heritage, his style and strokes are unassuming. While still a student of art and graphic design at St. Patrick’s Art School, Singapore, Sunar exhibited his first works at the Shell Discovery Art Exhibition (1986). His submissions received commendation at the Australian Art Awards (1987) and IBM Art Award (1988). His Chinese ink works have often been mistaken to be by a Japanese artist. Attributing his achievements to his mentors Jaafar Latiff and Iskandar Jalil, Sunar has held numerous solo and group shows in Singapore, Malaysia, and the UAE. Sunar’s works can be found at the National Museum of Singapore, National University of Singapore, Development Bank of Singapore, residences of royal families from neighbouring countries, Taiwan, the UAE, and various corporate and private collections in Singapore and overseas.

Artist Statement

Through this exhibition, I explore the notions of home and cradle land, or land of origin. These works also pay tribute to my late father and his quest to trace and reconnect with his bloodline. Inspired by Gauguin’s introspective painting, similarly, I ask: Where do I come from? Who am I? Where do I go from here?

The Prambanan temple is the largest Hindu temple of ancient Java, and the first building was completed in the mid-9th century. It was likely started by Rakai Pikatan and inaugurated by his successor King Lokapala. Some historians that adhere to dual dynasty theory suggest that the construction of Prambanan probably was meant as the Hindu Sanjaya Dynasty‘s answer to the Buddhist Sailendra Dynasty’s Borobudur and Sewu temples nearby, and was meant to mark the return of the Hindu Sanjaya Dynasty to power in Central Java after almost a century of Buddhist Sailendra Dynasty domination. Nevertheless, the construction of this massive Hindu temple did signify a shift of the Mataram court’s patronage, from Mahayana Buddhism to Shaivite Hinduism.

A temple was first built at the site around 850 CE by Rakai Pikatan and expanded extensively by King Lokapala and Balitung Maha Sambu the Sanjaya king of the Mataram Kingdom. A short red-paint script bearing the name “pikatan” was found on one of the finials on top of the balustrade of Shiva temple, which confirms that King Pikatan was responsible for the initiation of the temple construction.[5]: 22

The temple complex is linked to the Shivagrha inscription of 856 CE, issued by King Lokapala, which described a Shiva temple compound that resembles Prambanan. According to this inscription the Shiva temple was inaugurated on 12 November 856.[5]: 20 According to this inscription, the temple was built to honor Lord Shiva, and its original name was Shiva-grha (the House of Shiva) or Shiva-laya (the Realm of Shiva).[6]

According to the Shivagrha inscription, a public water project to change the course of a river near Shivagrha temple was undertaken during the construction of the temple. The river, identified as the Opak River, now runs north to south on the western side of the Prambanan temple compound. Historians suggest that originally the river was curved further to east and was deemed too near to the main temple. Experts suggest that the shift of the river was meant to secure the temple complex from the overflowing of lahar volcanic materials from Merapi volcano.[7] The project was done by cutting the river along a north to south axis along the outer wall of the Shivagrha Temple compound. The former river course was filled in and made level to create a wider space for the temple expansion, the space for rows of pervara (ancillary) temples.

Some archaeologists propose that the statue of Shiva in the garbhagriha (central chamber) of the main temple was modelled after King Balitung, serving as a depiction of his deified self after death.[8] The temple compound was expanded by successive Mataram kings, such as Daksa and Tulodong, with the addition of hundreds of pervara temples around the chief temple.

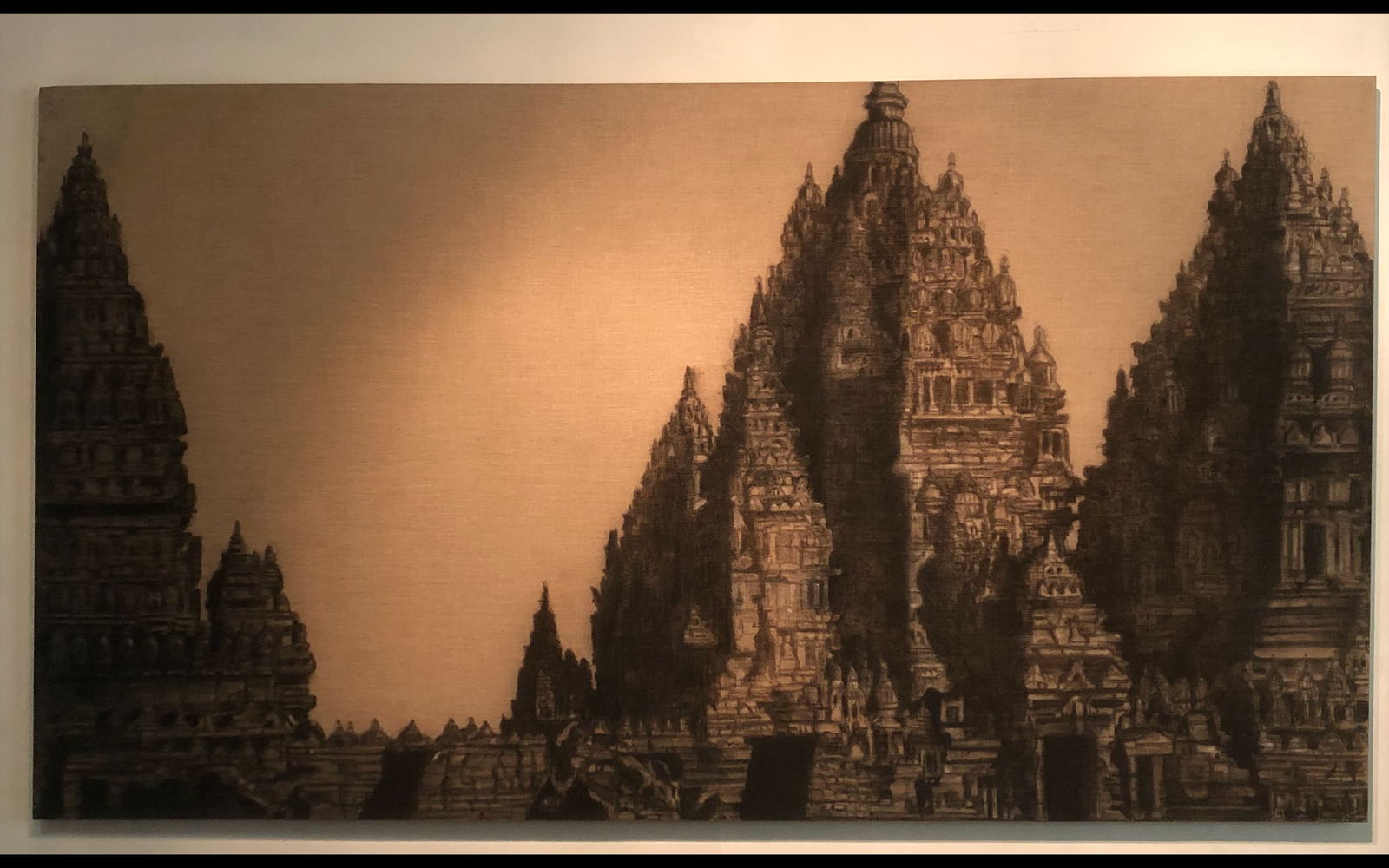

With main prasada tower soaring up to 47 metres high, a vast walled temple complex consists of 240 structures, Shivagrha Trimurti temple was the tallest and the grandest of its time.[1] Indeed, the temple complex is the largest Hindu temple in ancient Java, with no other Javanese temples ever surpassed its scale. Prambanan served as the royal temple of the Kingdom of Mataram, with most of the state’s religious ceremonies and sacrifices being conducted there. At the height of the kingdom, scholars estimate that hundreds of brahmins with their disciples lived within the outer wall of the temple compound. The urban center and the court of Mataram were located nearby, somewhere in the Prambanan Plain.

( WIKI )

D’où venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous? (Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?), 1897–98, oil on canvas, 139.1 × 374.6 cm.

In our increasingly perplexing world, there comes a time we need to reaffirm our ties with our roots and history.

In 1976, we decided to trace my father’s ancestry in Java, Indonesia. I was 15 years old. My father had never been to school because the family was poor. He left his homeland in the 1940s during the second world war and Japanese Occupation and travelled for 35 years, intending to eventually return to his hometown Pacing Village, Wedi, in Central Java. Perhaps he had felt homesick or the need to reconnect with his origin. As his first son, I endeavour to continue his legacy. My father taught me to truly think about the world, to observe our universe, critically yet without judgement.

My father was a man of few words, we communicated through a silent language, a dynamic I attribute to his Javanese trait and virtue of patience.

Embah Sukartana and Paliyem

Mum and dad

He taught me to never lose sight of where we come from, who we are, and where we go from there. When I met his parents and siblings, the reunion was joyful, everybody was emotional; the atmosphere was sublime. Together we visited Prambanan, a ninth-century Hindu temple compound in Yogyakarta in Central Java, a one-hour drive from our village. I have never seen a more beautiful, majestic megastructure. I would describe it with a thousand words but here was a sight I had no words for, like seeing the universe with new eyes, the beginning and the end of everything. I thought for certain I was in a dream.

Before he passed on, my father left to me this great treasure of our roots and relationships with our family. To this day, the family is still in close contact, because of his persistence and effort in reconnecting with our bloodline.

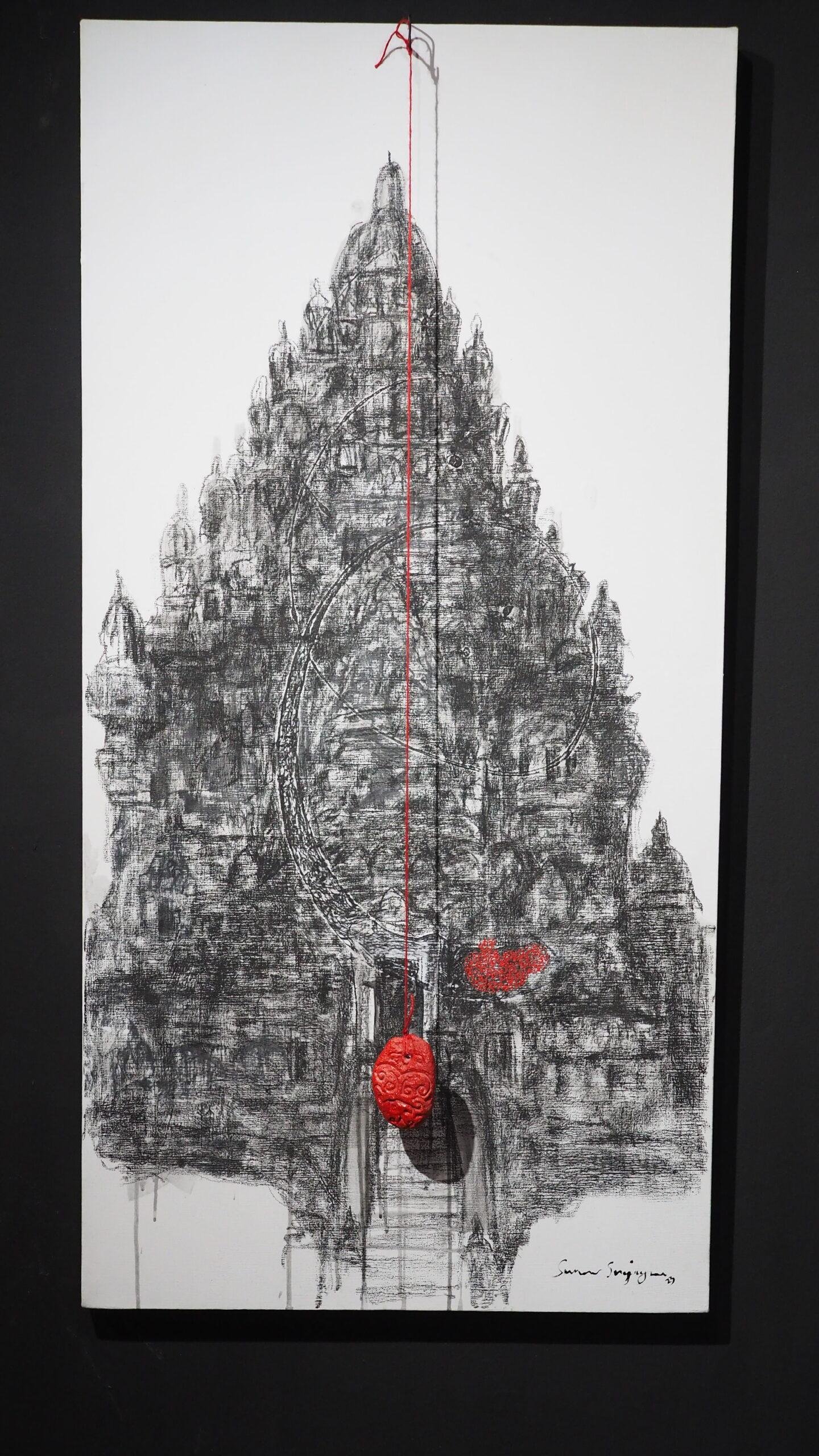

This painting Prambanan is made to honour my father

Prambanan, 2015, charcoal, graphite, pastel and oil stick on linen, 250 × 145 cm.

The Prambanan temple compound tells the story of family bond and history, roots, and memories that are transmitted through the generations. Rising like the Gunungan (Cosmic Mountain), Prambanan emerges like a cosmos unto itself that has revealed its eternal existence, the story of worlds, both the seen and the unseen.

According to folklore, was built in one night as the last temple in a marriage quest to build a thousand temples. In this Central Javanese tale, the kingdom of Prambanan was besieged by another kingdom. The war was lost to the invading kingdom who won through the supernatural powers of genies. The new king, Bandung Bondowoso, in order to marry the Prambanan princess, Loro Jonggrang, was challenged to the task of raising a thousand temples in one night. Faced with this seemingly impossible quest, the new king again borrowed the magic of his genie-soldiers. As they completed the 999th temple, Loro Jonggrang tricked the genie-soldiers into thinking dawn was breaking by burning straw and pounding mortars. Because genies feared sunlight, they were deceived by the light from the fire and household noise into believing the sun had risen and abandoned their construction duties. However, Bandung Bondowoso, possessing some magical power himself, completed the one-thousandth and last temple, which stands to this day and is known also as Loro Jonggrang temple.

In fact, the temple complex was initiated by Rakai Pikatan in the nineth century, with construction continuing and expanding through hundreds of years by the dynasties that followed.

The endurance of Prambanan teaches us valuable lessons about people and the state of the world, about not only the human nature of greed, power lust, and machinations, but also its strength in perseverance, resolution, and intelligence. Perhaps the reason for our existence is best communicated by an Australian Aboriginal proverb:

We are all visitors to this time, this place.

We are just passing through.

Our purpose here is to observe, to learn, to grow, to love

And then we return home.

Even though I started researching extensively on Javanese culture and traditions in 1985 during my first year at LASALLE College of the Arts, it took me 30 years to draw Prambanan, to put down on paper, with charcoal, graphite, pastel and oil sticks, the memories of a lifetime.